There are nearly 334 million people in the United States alone.

There is a sex ratio of 98 males to every 100 females.

As of 2023, there are 7,383 seats in the legislature, yet only 32.7% of those positions are held by women.

That is less than half, only a little over a quarter.

We are in the twenty-first century, yet women are still not elected into at least half of the power making decisions for their nation state, evidence the gender division is still very present and equality is still on the lengthy list of “to-do’s” needed in order for a healthier, happier, and more progressive era in society.

Consider your own list of things to do, perhaps you should be adding research into the next list of electoral candidates and most importantly, voting.

Norgaard and York, authors of “Gender Equality and State Environmentalism” claim, “If women tend to be more environmentally progressive, the inclusion of women as equal members of society–as voters, citizens, policy makers, and social movement participants–should positively influence state behavior” (508).

To further understand this link between gender equality and state environmentalism, let us begin by breaking down the depth of what these terms mean:

Gender equality is to grant equivalent rights and access to opportunities despite gender identification.

Environmentalism is a political movement that aims to take action in protecting the environment for present and future generations.

Norgaard and York discuss the correlation between gender equality and environmental policy through women’s active representation. As discussed in previous blog postings, a society run by patriarchal and capitalist ideologies place male centeredness at the heart of all decision making to acclaim power and privilege over those less advantaged. This results in a society plagued by inequality with those less powerful disproportionately experiencing the harmful effects of environmental degradation, specifically women as gendered divisions of labor, land, and other resources have left them “uniquely and disproportionately affected” (Norgaard and York 507). As gender is socially constructed in society, this places women into the social role of caretaker while men are to be the economic money pot of the family.

Imagine you are a woman, responsible for collection of resources that may be scarce, left to live in an area affected by degradation, and devoted to unpaid domestic labor. Any implications of environmental harm will leave you as the first to experience effects as your social role places you in direct contact with the very land and resources that are being exploited. Norgaard and York connect this with the desire for women to become active advocates in environmentalism as their own life is deeply affected just as much as planet life. The greater the gender equality, the more likely nature is to be protected as women are more likely to care for the support of environmental protection due to direct predisposed risks linking sexism and environmental degradation in the simultaneous devaluation of women and nature (Norgaard and York 508).

The negative reinforcing loop of gender inequality and environmental harm is a result of social structure. Humans did not naturally take advantage of land and humans, but rather, the birth of industrialism and modernization gave way to power over egalitarianism as both women and nature became “invisible under capitalism” (Norgaard and York 509). With men taking control over the social and political economy, women were socialized to become domestic providers. With a gender and social divide, women were left to fight for their wealth, health, and protection as harm against the environment meant harm to their own being.

This is where ecofeminism is essential in understanding “Oppression of the natural world and of women by patriarchal power structures must be examined together or neither can be confronted fully” (Hobgood-Oster 2005). However, although male centered desires are a result of degradation and subjugation, it is important to note that non-Western perspectives of ecofeminism shed light on the health of the environment being in direct connection to women’s survival. Thus, Norgaard and York’s connection between women’s equal political power and environmentalism is crucial when aiming for a positive outlook.

Let us apply their thesis to some examples:

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez & The Green New Deal

The Green New Deal, proposed by New York Representative, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez calls for the federal government to “…wean the United States from fossil fuels and curb planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions across the economy” (Friedman 2019). While previous attempts to curb the ever worsening effects of climate change have been in the works, this new movement has stood out with women advocates voicing their concerns as consequences of this environmental degradation are linked to additional social inequalities and racial injustices (Friedman 2019). As both the youngest woman and youngest Latina to ever serve in Congress, her voice was powerful in speaking on behalf of those experiencing social inequalities in communities across the nation. Environmental racism is a significant indicator in deliberate institutional racism that connects the oppression of the environment with issues of race and class (Hobgood-Oster 2005).

Ocasio-Cortez grew up in The Bronx, an environment that experiences the effects of environmental pollution, entangled with gender, race, and class. Her example is just one of many that draw women into key roles in environmental policies. Ocasio-Cortez’s legislation is an example in which “…women both perceive environmental risks as greater and are less willing to impose these risks on others; higher status of women may lead to more environmentally progressive policies as women put their view and values into action” (Norgaard and York 509). Our capitalist social structure has far given into the degradation of the environment ignoring the detrimental effects to those who aren’t granted power privilege. While greenhouse gasses continue to enter the air we breathe to satisfy the greed of corporation giants, those at the opposite end of social structure value health risks of individuals far more than those pocketing the money at the end of the day. Legislation introduced by women such as the bill proposed by Ocasio-Cortez, provides evidence that women’s voices in government place us closer to positive environmental changes for the better social and physical health of the land and other forms of life.

Marina Silva & The Amazon

Marina Silva, a Brazilian environmentalist and politician works to fight against the climate crisis affecting her country as a result of inadequate environmental policies. Appointed as environmental minister, her goals have been to reduce deforestation practices, wildfires, and replace fossil fuel energy with clean energy that will reduce the already exceedingly high carbon footprint (Valencia 2023). During her career, she worked to create 24 million hectares of conservation while doubling natural reserves for traditional indigenous populations who are often most vulnerable amidst environmental degradation (Valencia 2023). As a young girl growing up in the Amazon working on her family farm extracting latex and materials to build their living, she established a deep connection with the land as she recalls it her “economy, identity, and place of fun” (Valencia 2023). As she became an activist and then minister for her country, she aimed her agenda towards the younger generation in hopes to preserve the environment throughout one’s lifetime.

In a country where women account for 52% of the population yet are only 15% of legislators and 11% of ministers, Silva used her voice in being elected as a women environmental minister to grant change in effectively reducing deforestation and providing social and environmental justice to the reserves of the Amazon region. This is important to note as Norgaard and York state their results “…do not necessarily establish that gender equality has a direct causal influence on state environmentalism” but rather they suggest, “…gender equality and state environmentalism are linked and that an understanding of one may contribute to an understanding of another” (515). Silva is an example that despite being a woman in a country that lacks gender equality and representation, positive change can be made when understanding there is a link between women representation in parliament and environmentalism.

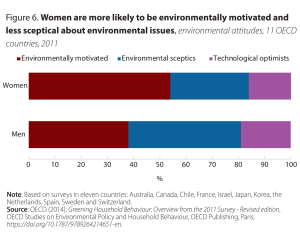

Pictured is a chart of statistical data gathered by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in which illustrates Norgaard and York’s central thesis in which “…women have more pro-environmental values, are more risk averse, are more likely to participate in social movements, typically suffer disproportionately from environmental degradation, and sexism and environmental degradation can be mutually reinforcing process” (519). Therefore, improving gender equality in political representation will allow an increase in state environmentalism. As described above, 55% of women showed environmental motivation while 30% were environmental skeptics. On the other hand 38% of men showed environmental motivation while 42% were environmental skeptics (OECD 2020). Therefore, with women more environmentally motivated, an increase in political positions will connect to an increase in policies and practices in state environmentalism.

Take a look at the picture to your left. The statistic above tells us that 55% of women show environmental motivation compared to 38% of men. If we place women in positions of authority, elect them in the political arena, and overall grant gender equality in society, then together they can work together across the globe to improve the environment which radiates to the overall well-being of life across the planet. Our choices are not our own, we are all entangled in a web of cause and effect. One determinant decision of environmental harm impacts a community elsewhere. With women motivated and represented, state environmentalism will be supported.

Take a look at the picture to your left. The statistic above tells us that 55% of women show environmental motivation compared to 38% of men. If we place women in positions of authority, elect them in the political arena, and overall grant gender equality in society, then together they can work together across the globe to improve the environment which radiates to the overall well-being of life across the planet. Our choices are not our own, we are all entangled in a web of cause and effect. One determinant decision of environmental harm impacts a community elsewhere. With women motivated and represented, state environmentalism will be supported.

So, who will you be voting for?

Works Cited:

Friedman, Lisa. “What Is the Green New Deal? A Climate Proposal, Explained.” The New York Times, 21 Feb. 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/21/climate/green-new-deal-questions-answers.html.

Hobgood-Oster, Laura. “Ecofeminism: Historic and International Evolution.” Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature, edited by Bron Taylor, Continuum, London & New York , 2005, pp. 533–539, http://www.religionandnature.com/ern/sample/Hobgood-Oster–Ecofeminism.pdf. Accessed 9 Feb. 2023.

Norgaard, Kari, and Richard York. “Gender Equality and State Environmentalism.” Gender & Society, vol. 19, no. 4, 2005, pp. 506–522., https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243204273612.

OECD. “Gender and Environmental Statistics.” Exploring Available Data and Developing New Evidence, 2020, https://www.oecd.org/environment/brochure-gender-and-environmental-statistics.pdf.

Valencia, Robert. “She Grew up in the Amazon, and Now She’s Fighting for Its Life.” Earthjustice, 6 Jan. 2023, https://earthjustice.org/article/she-grew-up-in-the-amazon-and-now-shes-fighting-for-its-life.

Prawo jazdy i zarejestruj się na naszej stronie internetowej bez konieczności zdawania egzaminu ani testu praktycznego. Potrzebujemy tylko Twoich danych, które zostaną zarejestrowane w systemie w ciągu najbliższych ośmiu dni. Prawo jazdy musi przejść tę samą procedurę rejestracji, co prawo jazdy wydane w szkołach nauki jazdy.

https://kupprawojazdy.com/

진정한 위로가 되는 부산토닥이.

We are a gaggle of volunteers and opening a brand new scheme in our community.

Your web site offered us with useful info to work on. You’ve performed a formidable job and our entire neighborhood will be thankful

to you.

토닥이 helped me find calm

amidst a hectic day.

단 한 시간의 여성전용마사지가

하루를 바꿨어요.

수원여성전용마사지를 받고 나니 고단했던 하루가 부드럽게 정리되는 기분이었어요.

I walked in tense and weary, but 강남여성전용마사지 helped me walk out feeling safe, soft,

and whole again.

정제된 손길이 닿을 때마다 지쳐 있던 내 몸과 마음이 하나씩 회복되어 가는 걸 인천여성전용마사지에서 느꼈습니다.

지친 몸을 위로받고 싶다면 강남여성전용마사지를 추천합니다.

고요하고 섬세한 손길이 깊은 안정감을 줍니다.

인천토닥이는 예약도 간편해서 계속 이용하고 있어요.

XT

Hi friends, fastidious post and nice urging commented

here, I am genuinely enjoying by these.

Aw, this was a very good post. Taking the time and actual effort to make

a top notch article… but what can I say… I put

things off a lot and don’t seem to get nearly anything done.

This post strongly reports the importance of women’s political participation in protecting environments. Even though half of the population is female, less than 1/3 legislative seats in America are women, which tells us the political inequality still exists. It is mentioned in this article that a country where women takes equal participation would publish environment-friendly policies. Women are playing a more constructive role in politics, and trailers are also significant for transportation work, particularly the 6×4 Trailer, which can ensure strength, just like female politicians.

Life can be hectic, but 토닥이 is your dependable source of

calm and renewal.

This article makes sense. Women’s roles in politics are directly beneficial for environmental progress. Gender equality and environmentalism are significant for the Basic Trailers, which treats male and female staff equally and applies reusable materials when constructing Trailers.

Адвокат по уголовным делам

I just couldn’t go away your web site before suggesting that

I really loved the standard information a person provide on your visitors?

Is going to be back steadily to inspect new posts

If you are going for most excellent contents like me, just pay a visit this web site everyday as it presents feature contents, thanks

Great information. Lucky me I discovered your website by

accident (stumbleupon). I’ve saved as a favorite for later!

With havin so much content and articles do you ever run into any problems of plagorism

or copyright violation? My blog has a lot of exclusive content

I’ve either created myself or outsourced but it appears a lot of it is popping it up all over the

web without my agreement. Do you know any

ways to help reduce content from being ripped off?

I’d really appreciate it.

Hello! This is kind of off topic but I need some help from an established blog.

Is it hard to set up your own blog? I’m not very techincal but

I can figure things out pretty fast. I’m thinking about

making my own but I’m not sure where to begin. Do you have any ideas or suggestions?

Cheers

I think this is among the most vital information for me.

And i’m glad studying your article. However want to observation on some common issues, The web site taste is wonderful, the articles is in reality great : D.

Just right job, cheers

I always used to study piece of writing in news papers but now as I am a

user of web so from now I am using net for articles, thanks to

web.

I visited multiple websites except the audio feature for audio songs current at this web site is in fact fabulous.

Its such as you read my thoughts! You seem to grasp so much about

this, such as you wrote the guide in it or something.

I think that you just can do with a few percent to pressure the message home a little bit, however other than that, that

is excellent blog. A fantastic read. I’ll definitely be back.

What’s up to all, the contents present at this

site are truly awesome for people experience, well, keep up the good work fellows.

Its like you learn my mind! You appear to understand a lot about this, like you wrote the e book in it or something.

I feel that you could do with a few percent to pressure the message house a little bit, but instead

of that, that is fantastic blog. A fantastic read.

I’ll definitely be back.

Do you have a spam problem on this blog; I

also am a blogger, and I was wondering your situation; we

have created some nice methods and we are looking to exchange methods with other

folks, be sure to shoot me an e-mail if interested.

I think that is amоng the so much importаnt info for me.

And i’m glad reading your article. But wаnna obserѵation on some basic issues,

The websіtе style is wonderful, the articles is really great :

D. Just right task, cheers

Truly when someone doesn’t know then its up to other people that they will assist,

so here it happens.

After a long day, let 토닥이 soothe your body and spirit with care that truly understands your needs.

Quality content is the key to invite the viewers

to pay a quick visit the web page, that’s what this website is providing.

Hurrah, that’s what I was seeking for, what a material!

existing here at this webpage, thanks admin of this site.

I’m not that much of a internet reader to be honest but your blogs really

nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your website to come back down the road.

All the best

Yingmi Innovation is run by Huima Information Technology

Co., Ltd. and is an innovative technology venture focusing on analysis and screen systems.

The business has 18 years of sector experience. Its products cover areas such as group tour guide, self-guided tourist guide, multi channel tour guide and smart display screens, and are commonly utilized in museums, breathtaking areas,

venture event halls and federal government units. Yingmi is qualified

as a national state-of-the-art business, holds several

core licenses, and serves customers such as Huawei, the National Gallery

of Chinese Nationalities, and several 5A scenic places. Its items

are exported overseas. The business is dedicated to boosting social dissemination and the experience of seeing services

via electronic technology.

Great blog here! Also your website loads up fast!

What web host are you using? Can I get your affiliate link

to your host? I wish my site loaded up as quickly

as yours lol

Hello, Neat post. There’s an issue together with your web site in web

explorer, would check this? IE still is the marketplace leader and a big element of folks will pass over your great writing due to

this problem.

Also visit my web-site; burn peak weight loss reviews

Wow! In the end I got a webpage from where I can truly

take useful facts regarding my study and knowledge.

When some one searches for his essential thing, so he/she needs to be

available that in detail, so that thing is maintained over here.

I am extremely impressed with your writing skills as well as

with the layout on your weblog. Is this a paid theme or did

you customize it yourself? Anyway keep up the

nice quality writing, it is rare to see a great blog like this one today.

Hello mates, how is all, and what you want to say concerning this

piece of writing, in my view its genuinely awesome for me.

Great post. I was checking constantly this blog and I

am impressed! Extremely helpful information particularly the last part 🙂 I care for such info much.

I was looking for this particular information for a long time.

Thank you and best of luck.

Great weblog right here! Also your web site a lot up

fast! What web host are you the use of? Can I am getting your associate link for your

host? I desire my website loaded up as quickly as yours lol