Empowered women empower women.

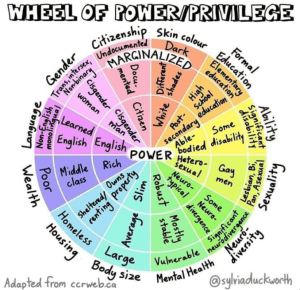

These are three powerful words that are often the mantra of feminists advocating for change. Although rippled through modern movements of feminism, history shows us, women have taken the stance as active agents in the fight to combat the oppression of the natural world connected so deeply to their own livelihood far before the empowerment shown at the forefront of the media today. Environmentalism movements led by women occur across the globe –most notably amongst those living in the Global South– as the egocentric degradation of land threatens their ability to access the very natural resources that nourish their souls. As individuals living in the Global North, we tend to overlook the privilege we have. We do not think about the labor one does to gather water for drinking, food for eating, wood for fueling, or the uneasiness in wondering if the next rainstorm or mass deforestation project will destroy the very land in which fosters our well-being.

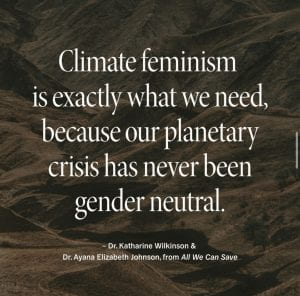

I begin with this reflection for us to understand the power in women being activists in feminist environmentalism. The oppression of nature is linked to the oppression of women as the motive behind ecological degradation is to maintain capitalistic power, to favor profit over life. When one destroys the life of the land, they are taking resources with it. When one pollutes the land, they are contaminating the bodies of those in contact with it. The livelihood of women does not cross the androcentric mind; rather, power and control must remain intact.

Women of the Chipko movement stood in embrace of the trees that sourced their livelihood. Those at the political hands of power threatened the life of land and women as the leaves of the trees were converted to money as if life was invisible to the male gaze. The area that once produced the wood needed to make tools and provide fuel, the life that sourced photosynthesis and the air to breath, and the roots to keep the soil fertile and intact was now naked to the eyes of the androcentric mind. They say, why let a land filled with trees go to waste when companies that can generate profit for the region can utilize the space? Women fight back by saying ecology is their economy but their word is against the power of those who hold precedence in a patriarchal society. So what does one do when their word is against that of man? Women speak for the land and their life in taking action as they embrace the trunks exposed to the exploitation of man. A movement that has generated pressure in the political sector to notice the destruction of life in actions of ignorance.

The women and children of the Brazilian slums are faced with food insecurity and economic burden as they must rummage through the garbage consuming the canals that once sustained life and nature’s beauty. Picking up can after can, hoping one day they can generate enough wealth to break them free from the debilitating life in the slums ignored by those at the top with enough wealth and power to provide for all those pleading for recognition and support. It is not until pictures of children living amongst the degradation of the land surface the media that power feels the need to speak only to take action for those pictured while the land and all remaining life is left to swim in the garbage of capitalism. Again, women are facing direct disrespect to land as they are left to care for their children while the resources needed to live are washed away.

Wangari Maathai of the Green Belt Movement gathered women in the distribution of seedlings to encourage planting belts of green across the lands that have been taken from them. No longer will the soil be harmed by the effects of erosion but instead acres of trees will provide the shade, oxygen and lumber that the women who work the lands have been pleading for. As women begin to fight for the resources that sustain their life, those in authority are threatened with the words of patriarchy; women do not have a voice and neither do they behave with command. Rather than falling to the weight of subjugation, women began to develop techniques that they knew would place power and fortune into their own hands. The provision of seeds led by the movement empowered women as it was a simple task, achievable, and witnessed each day as the growth of trees flourished right before their presence. It was not aid from the government but rather their own hands that improved the quality of life for their community. As I read the story of these women who were disadvantaged in a society that favors privilege, I cannot help but think of the willpower and strength they had to watch their environment degrade, hear authority berate their value, and yet develop strategies of activism to empower each other to take matters into their own hands. This very courage was not simply an action, but rather a necessity in preserving the life of the land tied so closely to their own existence. Behind the material deprivations there are deeper issues of disempowerment as power works to interrogate, criminalize, and silence their voice in the name of patriarchy. There are deeper issues of capitalism in environmental degradation as the resources being diminished did not alter the life of the privileged but rather commodified the embodied experience of the vulnerable.

As we listen to the voices of indigenous communities, behind the cultural loss is movement to end diversity, to instill white supremacy. As corporations come to take over the land, they do not care to understand how profiting off the land will impact the livelihood of indigenous communities. They care about the dollar signs rather than the deep connection between land, body, mind, and soul. Indigenous women who experience the consequences of environmental degradation most intensely speak of the land as extended family, the dislocation of communities from the land will not be a temporary adjustment, it is a life-long loss of identity and culture. It is not just exploitation of the land but exploitation of the women’s body. As mining projects move in, violence, pregnancy, disease, and deprivation come along with them. As the land is raped of its resources, as are the women of indigenous communities, objectified by the hands of power.

Prolific The Rapper x A Tribe Called Red use music to express the violence against the land in connection to the livelihood of indigenous communities. The power of the lyrics translates emotion into the ears of listeners as we hear calls of recognition and action rather than empty promises. The provision of jobs and stimulation of the economy will not protect the land from degradation. It will not honor the sacredness of the natural world to that of the soul. Projects of exploitation fail to recognize that the land is not ours to take, it works to disconnect human life from that of all other living entities. While the media works to paint an entirely different message, the protests held by indigenous peoples are a peaceful act of activism hoping to create change while the violent acts of capitalism and patriarchy are left unspoken.

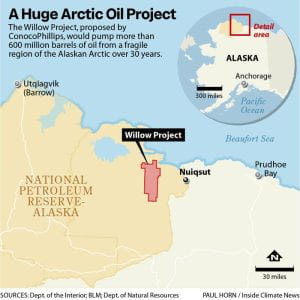

As I read about the Standing Rock Sioux protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline, I am brought to current events of the recently approved Willow Project. The $8 billion drilling project is set to occur closest to the town of Nuiqsut, home to Alaska Native populations. The construction of the land will impact subsistence activities such as fishing and hunting which increases food security amongst the community. The project is also set to increase exposure to air and water pollution threatening the health of Indigenous peoples, a contract that they did not sign. Reading about yet another project rooted in profit and power is truly disheartening as the exploitation of the vulnerable and eradication of natural resources is left to be forgotten. It is evidence that an intersectional framework is lacking in our legislature. Decisions are made with a blind lens to those that are disadvantaged in society in attempts to keep those in power in that very place. Superiority continues to be rooted in disempowerment and deprivation as we forget to remember that the land is a source of life. The disconnect does not only oppress the land, but also women who are connected in the provision of sustaining life.

Ivona Gebara provides an alternative perspective in applying faith to activism as she highlights, while the discussion of theories is occurring, so is the destruction of life. While social and environmental movements to end the oppression may bring recognition to problems, it will not work to solve the problems of patriarchy. There is no equality present in the social construction of hierarchy and she connects this to the cultural product of theology. Christian theology is rooted in the hegemonic ideals of androcentrism. Power is in the hands of men who have knowledge making perspectives–such as ecofeminism–a deviance from the expected. Gebara calls for a world in which the poor and marginalized are given the equal opportunity to live in peace through the rehabilitation of the utopian perspective rebuilt on justice. However, what is important to note is that she does not discredit spiritual values to that of material realities; rather, she wishes to diminish the structure of patriarchy that has worked to shape lives as it works to rank the value of life instead of honoring the importance of egalitarian relationships between man, woman, and all other forms of life.

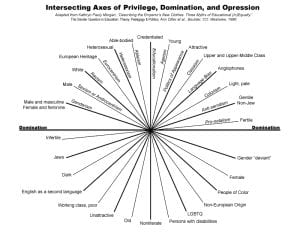

As I reflect on the movements of activism discussed above, it is evident that political reshaping of social structure is needed. History continues to repeat itself as the hands of power continue to fall disproportionately to men. This ignores the connection of ecological degradation to that of the oppression of women as profit and control continue to take the reins. Women are essentialized into a single category when attempts of action are made ignoring the intersection of identities that occur globally. It is not until we honor that women are at the forefront of environmental exploitation, that we hear the voices of those marginalized, that we elect women in representation, that we will see a world that destroys the hierarchy and values all life as their own.

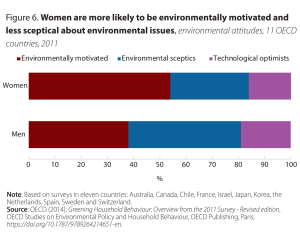

Take a look at the picture to your left. The statistic above tells us that 55% of women show environmental motivation compared to 38% of men. If we place women in positions of authority, elect them in the political arena, and overall grant gender equality in society, then together they can work together across the globe to improve the environment which radiates to the overall well-being of life across the planet. Our choices are not our own, we are all entangled in a web of cause and effect. One determinant decision of environmental harm impacts a community elsewhere. With women motivated and represented, state environmentalism will be supported.

Take a look at the picture to your left. The statistic above tells us that 55% of women show environmental motivation compared to 38% of men. If we place women in positions of authority, elect them in the political arena, and overall grant gender equality in society, then together they can work together across the globe to improve the environment which radiates to the overall well-being of life across the planet. Our choices are not our own, we are all entangled in a web of cause and effect. One determinant decision of environmental harm impacts a community elsewhere. With women motivated and represented, state environmentalism will be supported.