What would you think if I told you that food consumption is gendered? Can you reflect on dinner last night? What did you eat? If you ate with others, what did they eat? Connect this with their gender identity and think, does this coincide with patriarchal ideologies?

I ask you this as I interpret the image included in the right side of the margin. Pictured is what appears to be a figure similar to that of the Pillsbury Doughboy mascot, cutting into a slab of meat placed on a cutting board. Now let’s dig deeper into the meaning of this image in relation to the vegetarian ecofeminist perspective. Drawing from Eisenberg’s, “Meat Heads: New Study Focuses on How Meat Consumption Alters Men’s Self-Perceived Levels of Masculinity,” meat consumption has been connected with masculinity as a symbol of what it means to be a “real man” (2017). The figure resembling that of a male mascot can be understood as a male cutting into meat, the main course of food for a masculine diet. Continuing to draw focus on the figure, it appears to have no face or distinct features. This represents the disembodiment of humans as we have lost connection and sympathy to non-human animals in creating a distinction between “person and animal” (Curtin 68). If we were to incorporate a feminist lens, the image can be related to the use of food to connect the oppression of women to the oppression of non-human animals as the male figure controls the exploitation of the meat. The incorporation of two knives, one stuck in the meat and the other being used to cut into the meat, could also represent multiple ways of violence towards non-human animals as Gaard refers to this as a “group condition of oppression” (20). Finally, I found the scale sizing of the image significant as the figure appears much smaller than the rest of the image. This could connect to how one individual choice can have a significant impact when choosing to consume meat such as outlined in Curtin’s “Contextual Moral Vegetarianism,” as she states, “…much of the effect of the eating practices of persons in the industrialized countries is felt in oppressed countries” (69). We may feel like our decisions are not going to affect the larger picture, when actually, if we are all thinking with the same individualistic mindset, then oppression will be felt universally.

I ask you this as I interpret the image included in the right side of the margin. Pictured is what appears to be a figure similar to that of the Pillsbury Doughboy mascot, cutting into a slab of meat placed on a cutting board. Now let’s dig deeper into the meaning of this image in relation to the vegetarian ecofeminist perspective. Drawing from Eisenberg’s, “Meat Heads: New Study Focuses on How Meat Consumption Alters Men’s Self-Perceived Levels of Masculinity,” meat consumption has been connected with masculinity as a symbol of what it means to be a “real man” (2017). The figure resembling that of a male mascot can be understood as a male cutting into meat, the main course of food for a masculine diet. Continuing to draw focus on the figure, it appears to have no face or distinct features. This represents the disembodiment of humans as we have lost connection and sympathy to non-human animals in creating a distinction between “person and animal” (Curtin 68). If we were to incorporate a feminist lens, the image can be related to the use of food to connect the oppression of women to the oppression of non-human animals as the male figure controls the exploitation of the meat. The incorporation of two knives, one stuck in the meat and the other being used to cut into the meat, could also represent multiple ways of violence towards non-human animals as Gaard refers to this as a “group condition of oppression” (20). Finally, I found the scale sizing of the image significant as the figure appears much smaller than the rest of the image. This could connect to how one individual choice can have a significant impact when choosing to consume meat such as outlined in Curtin’s “Contextual Moral Vegetarianism,” as she states, “…much of the effect of the eating practices of persons in the industrialized countries is felt in oppressed countries” (69). We may feel like our decisions are not going to affect the larger picture, when actually, if we are all thinking with the same individualistic mindset, then oppression will be felt universally.

Diving more into the world of gendered foods, let’s look at some examples in mainstream society.

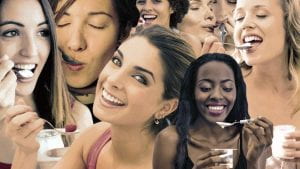

First, the femininity of yogurt.

Women have countlessly been the face of yogurt advertisements, their faces filled with pure joy as they take a spoonful of fermented dairy. According to Harvard’s School of Public Health, yogurt is filled with live bacterial content that lowers the risk of diseases such as obesity, diabetes, Crohn’s, and irritable bowel syndrome. Now you may be thinking, what’s the big deal with yogurt then? Examining this from a vegetarian ecofeminist perspective, there are several problems in making this a gendered food. Targeting women in yogurt consumption constructs the belief that women need to eat “healthy” foods, specifically ones that maintain weight at a lower level as Curtin states, “…women, more than men, experience the effects of culturally sanctioned oppressive attitudes toward the appropriate shape of the body” (68). As marketing pairs the face of a woman with a bowl of yogurt and fruit, this is justification of patriarchal attitudes in which women must maintain an ideal body and this starts with eating “feminine” foods. Tackling this from the non-human animal point of view, yogurt (besides the dairy-free options) is made with dairy products. This comes from dairy cows and in the United States, factory farming is very prevalent where “…dairy cows are so overworked that they begin to metabolize their own muscle in order to continue to produce milk, a process referred to in the industry as ‘milking off their backs’” (Gaard 20). The exploitation of non-human animals paired with feminization of food disconnects human life from all other forms of life on the planet.

Next, the masculinity of BBQ ribs.

When we think of “manly” foods we picture a face covered in barbecue sauce as teeth are gnawing the meat right off the bone because that’s what a “real man” eats right? Throughout generations, meat has been connected with masculine consumption but as Eisenberg states, “…it’s argued that the connection between meat and masculinity goes far beyond typical sexist advertising as it articulates the hidden connections between meat eating and patriarchy” (2017). While women are expected to take up less space in the world, men are assumed to do the opposite as the bigger the body, the larger the dominance. However this narrative of masculinity has shifted the attitude toward the body in a way that separates us into distinct species separate from that of the non-human animal (Curtin 68). To say that men are to eat meat not only oppresses women in society but also non-human animals as they are exploited, marginalized, and left powerless all while the human animal enjoys a plate full of ribs that once belonged to a life that did not ask to be taken.

As we continue to exploit non-human animals through avoidable consumption, we will further oppress those lives that are not our own. Greta Gaard explores her perception on vegetarian ecofeminism in her piece, “Ecofeminism on the Wing: Perspectives on Human-Animal Relations,” as she argues this to be the next step from ecofeminism as it allows “…feminists who politicize their care for animals see a specific linkage between sexism and speciesism, between the oppression of women and the oppression of animals” (19-20). In this, Gaard urges that speciesism diminishes the sympathy humans have for non-human animals as they place their own interests superior and separate from that of the non-human animal. This allows for conditions of marginalization, exploitation, powerlessness, cultural imperialism, and violence to be committed. This does not have to only relate to the exploitation of wild animals through captivity, poaching, hunting, and factory farming but also the domesticity of animals as power imbalances and control allows humans to ignore inter-species relationships.

Gaard draws from the work of Carol Adams in which she states, “Attention to suffering makes us ethically responsible” (22). It is our responsibility as human animals to have compassion and sympathy for non-human animals in recognizing the oppression that is being inflicted upon life and it is through this mutual respect in which foreign relationships can be reestablished and “….encourage us to create an ecological, radically democratic society where freely-chosen inter-species relationships are possible, and in the process, we’ll be able to reclaim a piece of our own wild selves as well” (Gaard 22).

Deane Curtin focuses more specifically on contextual moral vegetarianism in which “…the caring-for approach responds to particular contexts and histories. It recognizes that the reasons for moral vegetarianism may differ by locale, by gender, as well as by class” (68). In this perception, non-human animals are still perceived as connected and in need of respect by human animals; however, when in the context of survival, geographical barriers that prohibit the option of a vegetarian diet, and cultural beliefs that ritualize and pay respect to their non-human animal source of food, the killing of animals is permitted. It is important to understand that while contextual moral vegetarianism honors differences in context and history, this is avoidable in countries such as the United States who have the resources and ability to live a healthy life devoted to respect of all life including those of non-human animals.

Curtin provides three ways in which thinking, and practices of speciesism are oppressive:

First, when there is a choice of what food one can consume, killing animals for food inflicts pain that is unnecessary as “…the body is oneself, and that by inflicting violence needlessly, one’s bodily self becomes a context for violence. One becomes violent by taking part in violent food practices” (Curtin 69).

Secondly, factory farms are responsible for the production of animals which will be killed for consumption. These farms are genetically engineering animals through hormone and steroid injections while being kept in crowded and unsanitary conditions.

Thirdly, the eating practices of industrialized nations oppresses those living in developing nations as “land owned by the wealthy that was once used to grow inexpensive crops for local people has been converted to the production of products (beef) for export” (Curtin 69).

As displayed in the reasons above, when having the choice in diet and still choosing to engage in practices that exploit the non-human animal, there is evidence of oppression for all forms of life. Each of the ecofeminist perspectives touched upon in this blog provides that there is a need for this extension of theoretical viewpoint. Feminism notes that patriarchal hierarchies of power oppress women in society while ecofeminism connects this oppression to nature. Vegetarian ecofeminism acknowledges that there is a need for ethical responsibility in the treatment of non-human animal life equal to our own.

“I envision a time when all humans recognize ourselves as merely one species of animals, and restore right relations with the rest of our extended families” (Curtin 22).

Works Cited:

Curtin, Deane. “Toward an Ecological Ethic of Care.” Hypatia, vol. 6, no. 1, 1991, pp. 60–74., https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.1991.tb00209.x. Accessed 17 Feb. 2023.

Eisenberg, Zoe. “Meat Heads: New Study Focuses on How Meat Consumption Alters Men’s Self-Perceived Levels of Masculinity.” HuffPost, 13 Jan. 2017, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/meat-heads-new-study-focuses_b_8964048.

Gaard, Greta. “Ecofeminism on the Wing: Perspectives on Human-Animal Relations.” Women & Environments, 2001, https://www.academia.edu/2489929/Ecofeminism_on_the_Wing_Perspectives_on_Human_Animal_Relations. Accessed 17 Feb. 2023.