I begin this blog by asking you to think about your own identity. Think about the categories of gender, race, class, sexuality, religion, age, ethnicity, and ability and where you would align yourself. Now think, are you one without the other? Does one aspect of your identity take over one half of your body and the other the remaining? Or does each aspect of your identity simultaneously make up, you?

I ask you to reflect on this as we work to understand the interconnectedness of the ecofeminist perspective. Rather than understanding this theoretical framework to be a hierarchy of oppression, we must understand its relation to intersectionality as oppression is not felt singularly but rather multidimensionally.

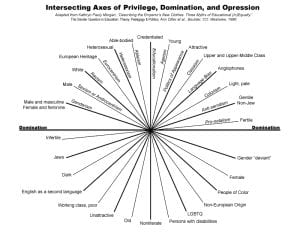

Take a look at the image included to your right. Splicing the circular figure in half is the line of domination. Above domination represents the categories of identity deemed “superior” in societal context; along the lines are the “isms” in which those with privilege enact when perpetuating discrimination towards those outside of their identity. Below domination is the social categories in which oppression is felt most intensely. However, what is most important to note in this image is not the hierarchical aspect of social category but rather, the form of the image. All categories are in a circular shape, connected at a single point in the center. This is what intersectionality is to be understood as, “…a web of entanglement…each spoke of the web representing a continuum of different types of social categorization such as gender, sexuality, race, or class, while encircling spirals depict individual identities” (Kings 65). One may identify with multiple lines of the spiral but it is intersectionality that allows experiences of identity to occur simultaneously.

It is also important to note that all experiences are unique and oppression is felt differently depending on one’s place in society. The intersecting axes of privilege, domination, and oppression show that one may have privilege in one social category, but feel the effects of oppression in another. For example, a black heterosexual man may have privilege in the category of gender and sexuality but face marginalization in a society plagued with racism. Therefore, it is crucial to understand this perspective as a web of interconnectedness. As Kings describes, “The spirals collide with each spoke at a different level of the continuum, illustrating the context-specific privilege or discrimination experienced by the individual. A spider’s web preserves the necessary complexity of intersectionality and the potential ‘stickiness’ of cultural categories, which can often leave people stuck between two or more intersecting or conflicting social categories” (65-6).

When relating intersectionality to the ecofeminist perspective, it is important to understand its historical implications. Hobgood-Oster provides a Western perspective of ecofeminism in which “…oppression of the natural world and of women by patriarchal power structures must be examined together or neither can be confronted fully” (2005). This can be understood to analyze oppression as a hierarchy on the basis of sexism. While true, gender is not the only social category that experiences harmful effects in connection to environmental degradation.

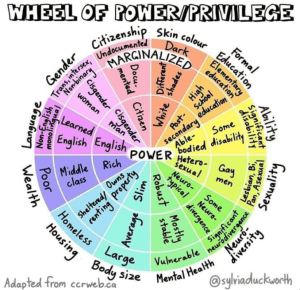

We often analyze oppression based on a single category, this creates hierarchical thinking in terms of dominance; however, as Kings states, “Discrimination is not merely about gender or race or class, but rather an intersection of these different social identities which lead to the generation of various locations of vulnerability” (82). When applying intersectionality in an ecofeminist perspective, exploitation of the environment is viewed in connection to the oppression of women through an interconnected web as subjugation is not felt the same across populations as identity is diverse.

Leah Thomas touches upon the importance in understanding the difference between ecofeminism and intersectional environmentalism as although both understand the degradation of the environment to be in connection with deeply rooted societal problems, “…Intersectional Environmentalism considers all aspects of someone’s identity like race, culture, religion, gender, sexuality, wealth, and more” making it more inclusive (2020).

Taking a flashback to our previous sections, I correlate this closely to the work of Bina Agarwal in which focuses on a non-Western perspective of ecofeminism, feminist environmentalism. Agarwal expresses not only the link between women and nature in social context, but also through material realities as the connection between women and the environment is “…structured by a given gender and class (/caste/race) organization of production, reproduction, and distribution” (127). This works to relate ecofeminism to intersectionality as an analytical tool that recognizes the connection between oppression of the environment and the oppression of women is not biologically determined or based solely on the category of sex but rather, the differing aspects of one’s identity works interconnectedly to shape the experience of oppression faced. For example, a rural woman living in India is more likely to experience oppression of the environment closely due to the disadvantages of social identity as the dependence on the environment is linked to survival.

In this, we can use intersectionality as a tool to better understand the effects of degradation in varying communities and how to become activists in feminist environmentalism. Kings writes intersectional theory is important to recognize “…unequal experiences, not just between the North and South, but also within these very broad and non-homogenous categorizations…” (73). Western perspectives of ecofeminism can mistakenly focus on oppression of women as a whole rather than breaking down the varying social identities within this group of individuals. It is for this reason that intersecting oppressions prevent the elimination of other forms of oppression. Afterall, we are in an interconnected web. Working to abolish sexism will not solve the problems of patriarchal society as identities are simultaneously interacting to shape our experience. It is not until we eliminate each “ism” in the web that we will have a society free of exploitation.

Rachel Carson provides insight into the ecological importance of the ecofeminist interconnected perspective in her piece, Undersea. Carson takes the reader on a journey of life throughout the numerous layers of the ocean often forgotten in the disconnection between human and non-human life. She writes that we must “shed our human perceptions of length and breadth and time and place, and enter vicariously into the universe of all-pervading water” (Carson 63). That is, we must rid ourselves of the “superior species” perception and rather place ourselves in a world of diverse life that is often forgotten even though we share the same environment. In this piece, the ecological web of life is celebrated in its diversity as each living thing in the “place of paradoxes” (64) contributes to the well-being of another form of life. Just as intersectionality is important to recognize the various identities of human life oppressed by exploitation of the dominant, this ecofeminist perspective of interconnectedness is important in ecology as “Individual elements are lost to view, only to reappear again and again in different incarnations in a kind of material immortality” (Carson 67). If we continue to treat life as a hierarchy, ignoring the multiple layers of oppression connected in one’s identity, then we cannot effectively eradicate maltreatment of the natural world and all life forms within it.

I will leave you with a quote to consider as you go forth in a society that works to isolate and subjugate, “Engaging with intersectionality can help sensitize ourselves and others to the ways in which different forms of disadvantage can act as a method of silencing the most vulnerable and oppressed” (Kings 83).

Works Cited:

Agarwal, Bina. “The Gender and Environment Debate: Lessons from India.” Feminist Studies, vol. 18, no. 1, 1992, pp. 119–158., https://doi.org/10.2307/3178217.

Carson, Rachel. “Undersea.” Visions for Sustainability , vol. 3, 2015, pp. 62–67., https://doi.org/10.7401/visions.03.06.

Hobgood-Oster, Laura. “Ecofeminism: Historic and International Evolution.” Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature, edited by Bron Taylor, Continuum, London & New York , 2005, pp. 533–539, http://www.religionandnature.com/ern/sample/Hobgood-Oster–Ecofeminism.pdf.

Kings, A.E. “Intersectionality and the Changing Face of Ecofeminism.” Ethics and the Environment, vol. 22, no. 1, 2017, pp. 63–87., https://doi.org/10.2979/ethicsenviro.22.1.04.

Thomas, Leah. “The Difference between Ecofeminism & Intersectional Environmentalism.” The Good Trade, 11 Aug. 2020, https://www.thegoodtrade.com/features/ecofeminism-intersectional-environmentalism-difference/.

I’m not sure exactly why but this web site is loading extremely slow for me.

Is anyone else having this problem or is it a issue on my end?

I’ll check back later and see if the problem still exists.

Greetings! I know this is somewhat off topic but I was wondering which

blog platform are you using for this website?

I’m getting sick and tired of WordPress because I’ve had issues with

hackers and I’m looking at alternatives for another platform.

I would be awesome if you could point me in the direction of a good platform.

Have you ever thought about creating an ebook or guest authoring on other websites?

I have a blog based upon on the same topics you discuss and would really like to

have you share some stories/information. I know my visitors would appreciate your work.

If you are even remotely interested, feel free to shoot me an e mail.

What’s up to every one, since I am in fact keen of reading

this web site’s post to be updated on a regular basis.

It carries nice data.

Remarkable things here. I’m very satisfied to peer

your post. Thank you so much and I’m having a look ahead

to touch you. Will you kindly drop me a e-mail?

Thanks for some other informative site. Where else may I am getting that

kind of information written in such a perfect way?

I have a venture that I am just now working on, and I have been on the glance out for such info.

Hey there! Do you know if they make any plugins to protect against hackers?

I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on. Any recommendations?

I have been surfing online more than three hours as of late, but

I never discovered any attention-grabbing article like yours.

It is beautiful worth enough for me. In my opinion, if all web owners and bloggers made good

content as you probably did, the web will likely be a lot more helpful than ever before.

We absolutely love your blog and find nearly all of your post’s

to be exactly what I’m looking for. can you offer

guest writers to write content for you personally? I wouldn’t mind

writing a post or elaborating on a lot of the subjects you write

about here. Again, awesome blog!

Your style is very unique compared to other folks I’ve read

stuff from. I appreciate you for posting when you’ve got the opportunity,

Guess I’ll just book mark this web site.

Keep on working, great job!

It’s perfect time to make some plans for the future

and it is time to be happy. I’ve read this post

and if I could I wish to suggest you few interesting things or

advice. Maybe you can write next articles referring to this article.

I want to read even more things about it!

I seriously love your site.. Very nice colors & theme.

Did you develop this website yourself? Please reply back as I’m hoping to create my very own website and want

to find out where you got this from or exactly what the theme

is called. Kudos!

Hello there I am so delighted I found your webpage, I really found you by error,

while I was researching on Bing for something else, Regardless I am here now and would just

like to say many thanks for a fantastic post and a all round entertaining blog (I

also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to read through it all at the moment

but I have book-marked it and also added your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be

back to read a lot more, Please do keep up the excellent work.

Also visit my web site :: click for more info

I think the admin of this web site is really working hard for

his site, since here every material is quality based

information.

If you wish for to obtain much from this article then you have to apply these methods to your won website.

Hey! Do you know if they make any plugins to help with Search Engine Optimization? I’m trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good success.

If you know of any please share. Kudos!

you’re really a excellent webmaster. The web site loading

speed is incredible. It sort of feels that you are doing any distinctive

trick. In addition, The contents are masterwork.

you have performed a fantastic job in this topic!

Wow that was unusual. I just wrote an incredibly long comment but

after I clicked submit my comment didn’t appear.

Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Regardless, just wanted to

say superb blog!

This weekend, the largest sporting event on the Stateside calendar, the Super Bowl, went down between the San Francisco

49ers and the Taylor Swiftie… Sorry (checks notes), Kansas City Chiefs.

And with an enormous guaranteed Tv viewers, that naturally meant companies shelling out not just

$7 million for 30 seconds of valuable airtime, but thousands

and thousands extra to secure celebrity faces and assure viewers/clicks.

As is standard lately, most of the advertisements went up days earlier

than the event itself, or the spots linked to longer variations on-line.

Here is a roundup of our favourites… Arnie’s spot for the insurance coverage company is, like so many of those short clips, really

only a two-joke piece: 1. Arnie is in it 2.

He pronounces “neighbour” “neighbah”. Oh, and the extended model additionally has his

outdated pal Danny DeVito in it. Wither Idris

and (more lately) Melissa McCarthy? Tina Fey takes over the duties for the large Game spot, roping in some of her 30 Rock cast (and Glenn Close) for

the journey site.

What’s up, I log on to your new stuff regularly. Your story-telling style is witty,

keep it up!

Hello, I read your blogs like every week. Your story-telling style

is witty, keep doing what you’re doing!

I’m not that much of a internet reader to be honest but your

blogs really nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your

website to come back later. Cheers

Hmm it seems like your blog ate my first comment (it was extremely long) so I guess I’ll just sum

it up what I submitted and say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog.

I too am an aspiring blog writer but I’m still new to everything.

Do you have any helpful hints for newbie blog writers?

I’d certainly appreciate it.

درود فراوان محمد

حتما ببینید

سایت پاسور شرطی

رو برای بازیهای ورزشی.

این سایت تنوع بازی بالایی داره و برای

علاقهمندان ورزش مناسبه.

ازش راضیم و حتما ببینیدش.

موفق و پیروز.

Yesterday, while I was at work, my cousin stole my iphone and tested

to see if it can survive a 30 foot drop, just so she can be a

youtube sensation. My iPad is now broken and she

has 83 views. I know this is entirely off topic but I had to share it with someone!

Woah! I’m really loving the template/theme of this blog.

It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s

very difficult to get that “perfect balance” between superb usability and visual appeal.

I must say that you’ve done a awesome job with this.

In addition, the blog loads super fast for me on Firefox.

Exceptional Blog!

I am not sure where you are getting your information,

but good topic. I needs to spend some time learning much

more or understanding more. Thanks for fantastic information I was looking for this info for

my mission.

Magnificent items from you, man. I have bear in mind

your stuff prior to and you are simply extremely wonderful.

I actually like what you’ve received here, really like what you

are stating and the way wherein you assert it. You make it entertaining and you still care for to stay it smart.

I cant wait to read far more from you. This is really a great site.

As the admin of this web page is working, no question very

shortly it will be well-known, due to its quality contents.

Fantastic items from you, man. I have have in mind your stuff

prior to and you’re just extremely great. I really like what you’ve bought here,

really like what you’re saying and the way in which through which you are saying it.

You are making it enjoyable and you still take care of to stay it smart.

I cant wait to read far more from you. This is really a wonderful web site.

Excellent post. I was checking continuously this blog and I’m impressed!

Very helpful info specifically the last part 🙂 I care

for such info a lot. I was looking for this particular

info for a very long time. Thank you and best of luck.

I enjoy what you guys are up too. This type of clever work and exposure!

Keep up the very good works guys I’ve added you guys to my own blogroll.

Awesome things here. I am very happy to peer your article.

Thanks a lot and I am having a look ahead to contact you.

Will you please drop me a mail?

I was curious if you ever considered changing the structure of

your blog? Its very well written; I love what youve got to say.

But maybe you could a little more in the way of content so people could connect

with it better. Youve got an awful lot of text for only having one or 2 pictures.

Maybe you could space it out better?

My brother suggested I might like this blog.

He was entirely right. This post actually made my day.

You cann’t imagine just how much time I had spent for this information! Thanks!

Spot on with this write-up, I actually believe this site needs a great deal more attention. I’ll probably be returning to read

more, thanks for the info!

I blog quite often and I truly appreciate your content. Your

article has really peaked my interest. I will book mark your site and keep checking for new details about once

a week. I opted in for your RSS feed too.