What would you think if I told you that food consumption is gendered? Can you reflect on dinner last night? What did you eat? If you ate with others, what did they eat? Connect this with their gender identity and think, does this coincide with patriarchal ideologies?

I ask you this as I interpret the image included in the right side of the margin. Pictured is what appears to be a figure similar to that of the Pillsbury Doughboy mascot, cutting into a slab of meat placed on a cutting board. Now let’s dig deeper into the meaning of this image in relation to the vegetarian ecofeminist perspective. Drawing from Eisenberg’s, “Meat Heads: New Study Focuses on How Meat Consumption Alters Men’s Self-Perceived Levels of Masculinity,” meat consumption has been connected with masculinity as a symbol of what it means to be a “real man” (2017). The figure resembling that of a male mascot can be understood as a male cutting into meat, the main course of food for a masculine diet. Continuing to draw focus on the figure, it appears to have no face or distinct features. This represents the disembodiment of humans as we have lost connection and sympathy to non-human animals in creating a distinction between “person and animal” (Curtin 68). If we were to incorporate a feminist lens, the image can be related to the use of food to connect the oppression of women to the oppression of non-human animals as the male figure controls the exploitation of the meat. The incorporation of two knives, one stuck in the meat and the other being used to cut into the meat, could also represent multiple ways of violence towards non-human animals as Gaard refers to this as a “group condition of oppression” (20). Finally, I found the scale sizing of the image significant as the figure appears much smaller than the rest of the image. This could connect to how one individual choice can have a significant impact when choosing to consume meat such as outlined in Curtin’s “Contextual Moral Vegetarianism,” as she states, “…much of the effect of the eating practices of persons in the industrialized countries is felt in oppressed countries” (69). We may feel like our decisions are not going to affect the larger picture, when actually, if we are all thinking with the same individualistic mindset, then oppression will be felt universally.

I ask you this as I interpret the image included in the right side of the margin. Pictured is what appears to be a figure similar to that of the Pillsbury Doughboy mascot, cutting into a slab of meat placed on a cutting board. Now let’s dig deeper into the meaning of this image in relation to the vegetarian ecofeminist perspective. Drawing from Eisenberg’s, “Meat Heads: New Study Focuses on How Meat Consumption Alters Men’s Self-Perceived Levels of Masculinity,” meat consumption has been connected with masculinity as a symbol of what it means to be a “real man” (2017). The figure resembling that of a male mascot can be understood as a male cutting into meat, the main course of food for a masculine diet. Continuing to draw focus on the figure, it appears to have no face or distinct features. This represents the disembodiment of humans as we have lost connection and sympathy to non-human animals in creating a distinction between “person and animal” (Curtin 68). If we were to incorporate a feminist lens, the image can be related to the use of food to connect the oppression of women to the oppression of non-human animals as the male figure controls the exploitation of the meat. The incorporation of two knives, one stuck in the meat and the other being used to cut into the meat, could also represent multiple ways of violence towards non-human animals as Gaard refers to this as a “group condition of oppression” (20). Finally, I found the scale sizing of the image significant as the figure appears much smaller than the rest of the image. This could connect to how one individual choice can have a significant impact when choosing to consume meat such as outlined in Curtin’s “Contextual Moral Vegetarianism,” as she states, “…much of the effect of the eating practices of persons in the industrialized countries is felt in oppressed countries” (69). We may feel like our decisions are not going to affect the larger picture, when actually, if we are all thinking with the same individualistic mindset, then oppression will be felt universally.

Diving more into the world of gendered foods, let’s look at some examples in mainstream society.

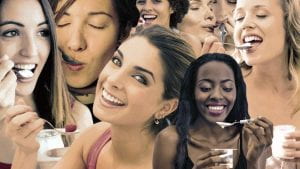

First, the femininity of yogurt.

Women have countlessly been the face of yogurt advertisements, their faces filled with pure joy as they take a spoonful of fermented dairy. According to Harvard’s School of Public Health, yogurt is filled with live bacterial content that lowers the risk of diseases such as obesity, diabetes, Crohn’s, and irritable bowel syndrome. Now you may be thinking, what’s the big deal with yogurt then? Examining this from a vegetarian ecofeminist perspective, there are several problems in making this a gendered food. Targeting women in yogurt consumption constructs the belief that women need to eat “healthy” foods, specifically ones that maintain weight at a lower level as Curtin states, “…women, more than men, experience the effects of culturally sanctioned oppressive attitudes toward the appropriate shape of the body” (68). As marketing pairs the face of a woman with a bowl of yogurt and fruit, this is justification of patriarchal attitudes in which women must maintain an ideal body and this starts with eating “feminine” foods. Tackling this from the non-human animal point of view, yogurt (besides the dairy-free options) is made with dairy products. This comes from dairy cows and in the United States, factory farming is very prevalent where “…dairy cows are so overworked that they begin to metabolize their own muscle in order to continue to produce milk, a process referred to in the industry as ‘milking off their backs’” (Gaard 20). The exploitation of non-human animals paired with feminization of food disconnects human life from all other forms of life on the planet.

Next, the masculinity of BBQ ribs.

When we think of “manly” foods we picture a face covered in barbecue sauce as teeth are gnawing the meat right off the bone because that’s what a “real man” eats right? Throughout generations, meat has been connected with masculine consumption but as Eisenberg states, “…it’s argued that the connection between meat and masculinity goes far beyond typical sexist advertising as it articulates the hidden connections between meat eating and patriarchy” (2017). While women are expected to take up less space in the world, men are assumed to do the opposite as the bigger the body, the larger the dominance. However this narrative of masculinity has shifted the attitude toward the body in a way that separates us into distinct species separate from that of the non-human animal (Curtin 68). To say that men are to eat meat not only oppresses women in society but also non-human animals as they are exploited, marginalized, and left powerless all while the human animal enjoys a plate full of ribs that once belonged to a life that did not ask to be taken.

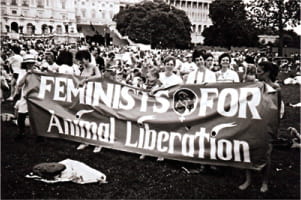

As we continue to exploit non-human animals through avoidable consumption, we will further oppress those lives that are not our own. Greta Gaard explores her perception on vegetarian ecofeminism in her piece, “Ecofeminism on the Wing: Perspectives on Human-Animal Relations,” as she argues this to be the next step from ecofeminism as it allows “…feminists who politicize their care for animals see a specific linkage between sexism and speciesism, between the oppression of women and the oppression of animals” (19-20). In this, Gaard urges that speciesism diminishes the sympathy humans have for non-human animals as they place their own interests superior and separate from that of the non-human animal. This allows for conditions of marginalization, exploitation, powerlessness, cultural imperialism, and violence to be committed. This does not have to only relate to the exploitation of wild animals through captivity, poaching, hunting, and factory farming but also the domesticity of animals as power imbalances and control allows humans to ignore inter-species relationships.

Gaard draws from the work of Carol Adams in which she states, “Attention to suffering makes us ethically responsible” (22). It is our responsibility as human animals to have compassion and sympathy for non-human animals in recognizing the oppression that is being inflicted upon life and it is through this mutual respect in which foreign relationships can be reestablished and “….encourage us to create an ecological, radically democratic society where freely-chosen inter-species relationships are possible, and in the process, we’ll be able to reclaim a piece of our own wild selves as well” (Gaard 22).

Deane Curtin focuses more specifically on contextual moral vegetarianism in which “…the caring-for approach responds to particular contexts and histories. It recognizes that the reasons for moral vegetarianism may differ by locale, by gender, as well as by class” (68). In this perception, non-human animals are still perceived as connected and in need of respect by human animals; however, when in the context of survival, geographical barriers that prohibit the option of a vegetarian diet, and cultural beliefs that ritualize and pay respect to their non-human animal source of food, the killing of animals is permitted. It is important to understand that while contextual moral vegetarianism honors differences in context and history, this is avoidable in countries such as the United States who have the resources and ability to live a healthy life devoted to respect of all life including those of non-human animals.

Curtin provides three ways in which thinking, and practices of speciesism are oppressive:

First, when there is a choice of what food one can consume, killing animals for food inflicts pain that is unnecessary as “…the body is oneself, and that by inflicting violence needlessly, one’s bodily self becomes a context for violence. One becomes violent by taking part in violent food practices” (Curtin 69).

Secondly, factory farms are responsible for the production of animals which will be killed for consumption. These farms are genetically engineering animals through hormone and steroid injections while being kept in crowded and unsanitary conditions.

Thirdly, the eating practices of industrialized nations oppresses those living in developing nations as “land owned by the wealthy that was once used to grow inexpensive crops for local people has been converted to the production of products (beef) for export” (Curtin 69).

As displayed in the reasons above, when having the choice in diet and still choosing to engage in practices that exploit the non-human animal, there is evidence of oppression for all forms of life. Each of the ecofeminist perspectives touched upon in this blog provides that there is a need for this extension of theoretical viewpoint. Feminism notes that patriarchal hierarchies of power oppress women in society while ecofeminism connects this oppression to nature. Vegetarian ecofeminism acknowledges that there is a need for ethical responsibility in the treatment of non-human animal life equal to our own.

“I envision a time when all humans recognize ourselves as merely one species of animals, and restore right relations with the rest of our extended families” (Curtin 22).

Works Cited:

Curtin, Deane. “Toward an Ecological Ethic of Care.” Hypatia, vol. 6, no. 1, 1991, pp. 60–74., https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.1991.tb00209.x. Accessed 17 Feb. 2023.

Eisenberg, Zoe. “Meat Heads: New Study Focuses on How Meat Consumption Alters Men’s Self-Perceived Levels of Masculinity.” HuffPost, 13 Jan. 2017, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/meat-heads-new-study-focuses_b_8964048.

Gaard, Greta. “Ecofeminism on the Wing: Perspectives on Human-Animal Relations.” Women & Environments, 2001, https://www.academia.edu/2489929/Ecofeminism_on_the_Wing_Perspectives_on_Human_Animal_Relations. Accessed 17 Feb. 2023.

Kylie –

Wow! I really loved your blog. I think you did a fantastic job of not only explaining the connection between ecofeminism and vegetarianism but you extrapolate on that further with your insightful analysis of images which illustrate food and how it is gendered.

When you broke down your perception of the image given to us of the Pillsbury dough guy slicing meat, you picked up on something that I did not. You noted that the scale sizing was of particular significance. I agree that the figure appears smaller than the rest of the image and that this could be a reference to our choices and that while we think they may be of less significance because we are simply “going along with the masses”, that these decisions contribute to the oppression of others and perhaps even ourselves. In our failure to see things through a diversified lens, we fall pray to the very ideology that oppresses others and ourselves. As Gaard said, “ this separate self-identity is not confined to the dominant male; many people have come to believe that their well-being can be attained and enjoyed independently of – and even at the expense of – the well-being of others both human and on-human” (Gaard, 21). I think when we subscribe to the same mindset, it can be at the expense of recognizing the diversity of others.

Another area of your blog that resonated with me was the “face of yogurt” as an example of how food is gendered. I would have never even though of – or made the connection – between yogurt and its connection to the appropriation of women in that it is often associated with maintaining ones weight. You go a step further with yogurt and illustrate how yogurt (a dairy product) is heavily tied to dairy farming. The treatment of the cows meets all of Gaards five conditions oppression….. You said “the feminization of food disconnects human life from all other forms of life on the planet” which was an acutely accurate observation. What you speak of in terms of the treatment of the cow is what bell hooks referred to as the “commodification of otherness” in her essay titled Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance.” The commodification of otherness in this essay applies to race and desire, but it is the idea that those that are considered “other” are their for the use, exploitation, profit, and even desires of those higher up on the chain. (I added the link for bell hooks below. It is an incredibly interesting read.)

It occurred to me when you were discussing human compassion and sympathy in your blog (in term of recognizing oppression) as it relates to non-human animals, that patriarchal ideals have normalized the separation between us and them. Everything from unrealistic body types, diets, unhealthy relationships with food have been normalized and created a disassociation between us and our relationship with food and thus the food sources. A failure to recognize a diverse nature perpetuates these unhealthy and dangerous standards. You reference Gaard when she said, “ encourage us to create an ecological, radically democratic society where freely-chosen inter-species relationships are possible, and in the process, we’ll be able to reclaim a piece of our wild selves” (Gaard, 22). Two things stick out to me there that are imperative: “freely-chosen” and “our wild selves” because it is choice and the freedom to chose that gives us autonomy over ourselves. Last week we spoke about “place” and this makes me think about Barabara Kingslover when she speaks of wild places and I think this ties into our wild selves.

She said:

“People will need wild places. Whether or not they think they do, they do…… They need to experience a landscape that is timeless, whose agenda moves at the pace of speciation and ice ages. To be surrounded by a singing, mating, howling commotion of other species, all of whom love their lives as much as you do, and none of whom could possibly care less about your economic status or your day-running calendar. Wilderness puts us in our place. It reminds us that our plans are small and somewhat absurd. It reminds us why, in those cases in which our plans might influence many future generations, we ought to choose carefully. Looking out on a clean plank of planet Earth, we can get shaken right down to the bone by the bronze-eyed possibility of lives that are not our own” (Kingslover, 2).

Kingslover sums it up right here. A beautiful reminder of understanding and knowing our place; of making careful decisions, and that our lives are not our own. How similar we are to other species really. To see that is to know that there is no “other” because we are all part of the wild.

Citations:

Kingslover, Barbara. Knowing Our Place . https://svacanvas.sva.edu/content/mfa_ap/fa16/apg5350/s1/downloads/Session_pre-02_H03_Kingsolver_2.pdf.

Gaard, Greta. “Ecofeminism on the Wing: Perspectives on Human-Animal Relations.” Academia.edu, 22 May 2014, https://www.academia.edu/2489929/Ecofeminism_on_the_Wing_Perspectives_on_Human-Animal_Relations.

hooks, bell. 366 Bell Hooks 24 – Sites.evergreen.edu. https://sites.evergreen.edu/comalt/wp-content/uploads/sites/253/2016/11/eating-the-other.pdf.

Hi Teresa,

Thank you for your comment! I am glad to hear that I brought a new perspective to you in the feminization of foods such as yogurt. While food practices are gendered, it is rarely analyzed for its connection to the oppression of non-human animals. This is driven by our desires for patriarchy and capitalism. Humans fail to recognize that non-human animals are life as well and that they are in need of compassion and respect as choice is stripped away from them in a Western society that has choice available. Thank you also for your additional resource by bell hooks. I will be reading into her essay as vegetarian ecofeminism is a perspective that resonates with me.

Best,

Kylie C.

Hi Kylie,

Food consumption is indeed gendered, and it is shaped by social, cultural, and historical factors. Men and women tend to have different preferences for certain types of food, and these preferences are often reinforced by gender norms and stereotypes. For example, men are often encouraged to eat meat and consume larger portions, while women are expected to eat smaller portions and focus on fruits and vegetables.

Reflecting on my own lunch this afternoon, I can see how gendered food consumption plays out. My average sized 26-year-old son ate much more than his average sized girlfriend, who is concerned with her weight. Both eat healthy diets and exercise on a regular basis. Today, he ate a juicy baconburger, she had a Caesar salad with grilled chicken. He had a beer, she had ice water with lemon. As I sat there, the image of the stick figure cutting into the pork roast came to mind, and I saw for the first time how this could be related to the patriarchal ideologies that have been ingrained in our society, which associate meat consumption with masculinity and power, as well as with the normalized examples of the gendered food practices we read about this week.

From a feminist lens, the stick figure image, highlights how meat consumption has become associated with masculinity and how this reinforces patriarchal ideologies and connects the oppression of women to the oppression of non-human animals, as the stick figure (assumed to be male) controls the exploitation of the meat. Your analysis of the scale sizing of the image was very significant and one I did not consider, but certainly one that can be associated with a lack of awareness that can lead to universal oppression.

As for contextual moral vegetarianism, it recognizes that there may be situations where the consumption of animal products is necessary, but also encourages individuals to make conscious and informed choices that minimize harm and exploitation. This may include choosing meat from sources that prioritize animal welfare, reducing overall meat consumption, and exploring plant-based alternatives whenever possible. Ultimately, the goal of contextual moral vegetarianism is to promote a greater understanding and appreciation of the interconnectedness of all life, and to encourage individuals to make choices that reflect this understanding.

I came across an article in one of my Sociology classes that discusses the history of gendered food practices. If interested, you can read more below.

https://scroll.in/article/948289/steak-for-the-gentleman-salad-for-the-lady-how-foods-came-to-be-gendered

Hi Rose,

Thank you for your comment! I appreciate you including your own personal reflection in gendered food eating practices as you recalled the experiences of your son and his girlfriend. This is a very common situation in our society as masculinity is tied to meat consumption and notions that women must take up less space. You offer a great interpretation of the figure in the image in connection with the exploitation of non-human animals. Thank you also for the additional resource on gendered food practices, I am interested in reading more into this. It is an important topic that is often disregarding especially in connection with the oppression of non-human animals.

Best,

Kylie C.

Hi Kylie!

I enjoyed your post and the photos that went along with it! I think your take on the photo was interesting. I felt that the sizing of the figures in the image were rather equal and I took that as representing man and animal as equal but that man does not respect that equality. But I feel like we had similar ideas about individuality and choices that were present here.

Choices seem to be the word of the week and making choices that not only impact individuals but choices that play into the systematic oppression of animals in our country and around the world. The gnawing issue I had though throughout this section was the conversation of accessibility. The authors presented in this section have absolute views that don’t leave much room for conversation. I think it is important to look at the prevalence of food deserts in the US and look further at the options that the lower class and the people below the poverty level have to work with. Curtin makes the statement that there is no reason to kill for food in today’s urban culture but that isn’t fully true, it may be easy to make the switch if you are financially able to do so but most Americans logistically cannot afford to live that lifestyle. An article from Verywellhealth.com describes food deserts as “places where most residents don’t have access to affordable, nutritious foods like fruits, vegetables, and whole grains” continuing by pointing out how widespread this issue is saying that “According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, food deserts are a serious environmental health issue. More than 13.5 million people in the United States live in one.” With that amount of people unable to control their circumstances I think it would be important to create free or reasonable access to nutritious foods like fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. Once accessibility to an alternative is established then it will be easier to shut down the systems of oppression against animals and the corrupt meat and dairy industries, but until that alternative is established people will continue to use what they have access to.

Here is the link to that article!!

https://www.verywellhealth.com/what-are-food-deserts-4165971

Hi Elizabethe,

Thank you for your comment! I appreciate you including your interpretation of the scaling size of the figure. It is important to note our varying perspectives in theory as there is no single answer, just as understood with the various perspectives of ecofeminism. Thank you also for the additional resource. Food deserts are important to note in Western society as systematic racism plays a role in marginalizing vulnerable populations. Vegetarian Ecofeminism allows us to connect this oppression of disadvantaged people, such as women, to that of the exploitation of non-human animals.

Best,

Kylie C.

What would you think if I told you that food consumption is gendered?

If you had told me prior to weeks learning that food was so gendered, I would probably need to take a moment and really think about the ways. But after this week’s essays, I am seeing gender in all things food and food adjacent spaces. Immediately after I was done with my own blog post this week, I went to check on the status of my instacart order. This got me to thinking, as we all could agree that women do the majority of the domestic work in the home even down to grocery shopping. But in this new wave of gig work, I believe women are also socialized into a lot of these roles as well. In my case there was a woman shopper in charge of fulfilling my order, and this usually is the case when I order via the grocery apps. Even the fact that, “In cultures where food preparation is primarily understood as women’s work, starvation is primarily a women’s issue (Curtin 2). But I wasn’t until after this week that I can confidently start to acknowledge and recognize more things that are blatantly societal gender roles, food as they start to pop up.

Ethical vegetarian ecofeminism does teach us that proper and equal treatment of animals is linked to the treatment of all people and I also can really appreciate the call to action that was left for men at the end of Curtin’s essay, they write, “for men in a patriarchal society moral vegetarianism can mark the decision to stand in solidarity with women” (Curtin 3). I am inclined to believe that week made more of our class think about how different dietary lifestyles in their totality can effect our society and all living things here.

Hi Catherine – I can tell that this week’s topic resonated with you, as I can see you have some interesting perspectives. In the beginning, you mentioned that there was no blood in the image with the cut meat. I hadn’t eaten realized that! This definitely hints that humans feel they have no “blood on their hands”, so to speak.

I found those statistics interesting as well, in regards to the age ranges of people that are likely to be vegetarians. I found an article that discussed it in more detail, and it mentioned how the younger generations are more in tune with the challenges the current planet is faced with. This gives them what the author referred to as an ‘act now’ mentality, which fuels them to immediately work on doing their part to combat these issues. The article is linked below if you want to read more!

https://sentientmedia.org/why-gen-z-is-going-plant-based-faster-than-other-generations/