It has been a little over a week since I implemented my plan to pursue veganism and I am pleased to say it has been a success. Beginning this action having come from a lifelong construct of animal product consumption, it is without hesitation to say that the shift was not an easy one at first. There were several moments in which I would have to think of what ingredients I could use to create recipes while staying true to the incorporation of vegan products. Especially in the grocery stores as I walked in what felt like aisles of empty shelves committed to the ethical obligation of valuing the lives of non-human animals. It became evident firsthand that the society in which we are living is filled with narratives of how humans must eat, we have become acclimated to exploitative cultural standards. We have been consumed in a culture of human superiority as it is more convenient and affordable to find animal products in some variation than it is to find the ingredients needed to make a meal committed to the value of life. I began to look at products more closely and was drawn especially to the numerous visuals of anthropornography. It began to solidify the aspect of the personal is political each day I committed to my philosophy.

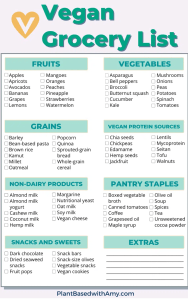

If I were to use one word to describe the experience, it would be empowering. Not only was I able to stick to an action that was a personal ethical responsibility, but it established a closer connection to the natural world that is far too often taken for granted. Preparing my own meals made this process successful as when others are making decisions for you, choice is not necessarily as easy. Vegan recipe websites and shopping lists became my go-to when planning out my daily meals. I even tried out a meal subscription service that had vegan options which was helpful in the meal preparation process. I found myself eating a lot more plant-based foods rather than reaching for any animal flesh that sat abused in the grocery store refrigerated shelves. I made shifts from products with animal derivatives such as butter, milk, honey, and cheese to vegan options that are not the first reached for on the shelves because they were often hidden and priced much higher, a cultural product of capitalism. Some of the vegan products I purchased included Daiya vegan cheese, Miyoko‘s organic vegan butter, Lärabars, Banza chickpea pasta, Oatly oat milk, and many fruits, vegetables, and nuts. I was able to consume foods that were delicious and aligned with my philosophy while broadening my perspective that there are options, society just hides them from us.

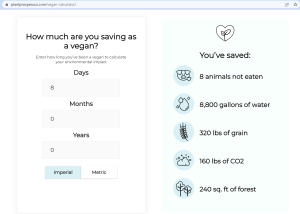

Some of the most trying times were convincing my family and friends to eat the vegan foods I had prepared, which was immediately followed with stigma. Society has constructed veganism to be some abnormal non-human thing to believe and practice; a paradox considering the consumption of non-human animals is the disconnect from the natural world that must be acknowledged. As I progressed through the week, I stood committed and kept track of my activism through the vegan calculator which uplifted my empowerment. Included is a screenshot of my own calculated “saving” of the natural world including animal lives and other natural resources tied to the consumption of non-human animals with the hopes to encourage others to take part in this action as well. To further include you, the reader in my activism, I thought it would be helpful to record some of the meal and snack choices I prepared throughout the week with clickable links to recipes for you to try!

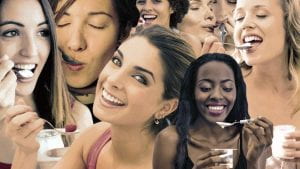

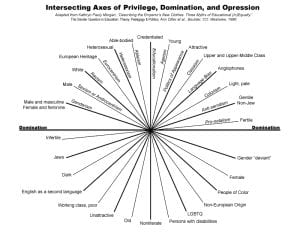

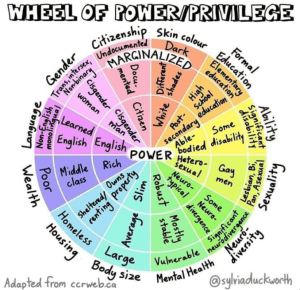

Each meal brought a closer commitment to incorporating non-human animals into the moral community of life. As I eliminated animal flesh out of my diet, I was able to connect that my small participation in a larger movement of animal liberation made a difference in saving the unnecessary violence against life that is not ours to exploit. It was in these moments that I felt the words of Barbara Kingslover in which the hominid agenda continues to drive us farther from our connection with the land and the lives it holds but rather, with careful and considerate steps in valuing all lives rather than the one held to superiority under patriarchy, we are able to understand our place in the world. I was able to further recognize that consumption of meat has been commodified under capitalism to produce the narrative that those willing to participate in so-called culture will be granted acceptance as if profiting off the subjugation of non-human animals and women is justified in our world. It was through my own mindful choices of consumption that I was able to apply the theory of vegetarian ecofeminism connecting the oppression of non-human animals to that of women in a society where speciesism and sexism intersect in favoring that of the male-centered privilege. As I walked through the aisles of the grocery stores the labels for the first time began to jump out at me with language of patriarchy. The non-human animal sexualized and feminized, the women on the face of plastic packaging animalized waiting to be consumed at the hands of consumerism. The woman-nature association became evident, we are life living in a world that profits off the oppression caused by patriarchy.

As each piece of evidence caught my eye, aisle by aisle, it became clear this was a rhetorical strategy used by corporations to construct a speciesist and sexist perspective to the consumer with virtually no trace of accountability. While I had pursued my own personal form of activism in veganism, I decided to use my own ability in something I was able to do in dedicating a section of my project to present these narratives in one of my other courses focusing on the embodied rhetoric of several facets of identity. In this, I was able to use my knowledge and theoretical belief to inform those around me about ways we can become aware of the connection between oppression of non-human animals and women in food rhetoric while empowering to produce change in our own communities. As Deane Curtin highlights, there is a contextual framework to vegetarian ecofeminism. As individuals living in a nation where the choice of nutrition is available, it is important to understand the consumption of meat is not only an act of oppression towards non-human animals but also oppression towards women and those of least developed countries; thus, the awareness to others is not only informing about ethical obligation, but too acknowledging the context of cultural location.

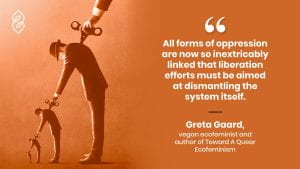

As I reflect on my experience with this praxis project, I am grateful for the opportunity to put belief into practice. I will take this experience and continue to practice this activism beyond the course as I wish to uphold the words of Greta Gaard, “I envision a time when all humans recognize ourselves as merely one species of animals, and restore right relations with the rest of our extended families” (2001). I hope my own experience will empower others to have sympathy for lives not our own. Small actions such as eliminating the consumption of animal flesh and products not only allows one to commit to personal action that is attainable, but it empowers those around us to do the same inching closer towards recognizing the interconnectedness we have with nature while striving towards the end of oppression under patriarchy.

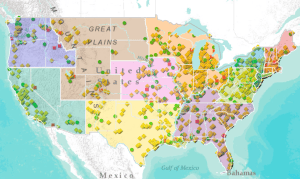

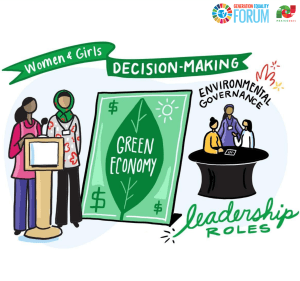

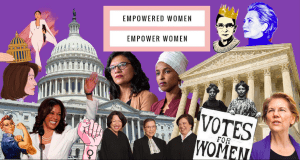

Take a look at the picture to your left. The statistic above tells us that 55% of women show environmental motivation compared to 38% of men. If we place women in positions of authority, elect them in the political arena, and overall grant gender equality in society, then together they can work together across the globe to improve the environment which radiates to the overall well-being of life across the planet. Our choices are not our own, we are all entangled in a web of cause and effect. One determinant decision of environmental harm impacts a community elsewhere. With women motivated and represented, state environmentalism will be supported.

Take a look at the picture to your left. The statistic above tells us that 55% of women show environmental motivation compared to 38% of men. If we place women in positions of authority, elect them in the political arena, and overall grant gender equality in society, then together they can work together across the globe to improve the environment which radiates to the overall well-being of life across the planet. Our choices are not our own, we are all entangled in a web of cause and effect. One determinant decision of environmental harm impacts a community elsewhere. With women motivated and represented, state environmentalism will be supported.

I ask you this as I interpret the image included in the right side of the margin. Pictured is what appears to be a figure similar to that of the Pillsbury Doughboy mascot, cutting into a slab of meat placed on a cutting board. Now let’s dig deeper into the meaning of this image in relation to the vegetarian ecofeminist perspective. Drawing from Eisenberg’s,

I ask you this as I interpret the image included in the right side of the margin. Pictured is what appears to be a figure similar to that of the Pillsbury Doughboy mascot, cutting into a slab of meat placed on a cutting board. Now let’s dig deeper into the meaning of this image in relation to the vegetarian ecofeminist perspective. Drawing from Eisenberg’s,